By Zoe Albert, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Anthropology, Boston University

My experience with primatology began on the other side of the globe in Costa Rica. Even though I was young and inexperienced, a Tulane PhD candidate saw my drive and passion and took a chance on me. The field proved to be challenging both mentally and physically. Despite this, I fell in love with primatology and the beautiful primates who allowed me the unique opportunity to bear witness to their lives.

Roughly midway through that first field season, I was on a follow observing an Alpha male capuchin named Cicatriz. I looked down at my tablet to record his behavior, sitting vigilantly, and when I looked up, I was met with a face full of mushy, seedy, insect laden monkey poop. While this may have been a career deal breaker for some, for me it felt reminiscent of Newton and his apple. I was a young scientist under a tree when inspiration fell from above. As I wiped his pungent poo off my face, and out of my hair, I couldn’t help but think of everything that I could learn from it. By simply observing his feces I could tell what he had eaten and get an overall sense of his health. If I had more tools, I was certain I could discover which offspring he had sired, and which microbes lived in his gut. Thus began my journey into the world of the primate gut microbiome, or the complex network of microbes that live within the gut of an animal and help it perform basic functions such as the fermentation of indigestible fiber.

Bottom: Visiting a school group with our Environmental Education team.

Now, as a 4th year PhD candidate in Dr. Cheryl Knott’s lab, those musings have become hypotheses and questions (i.e. how the gut microbiome responds to periods of low and high fruit; and, how the microbiome changes when orangutans are social). Since that first field season, I have taken courses, attended conferences, spoken with experts, and even attended a laboratory course in the Amazon jungle to gain the skills needed to test those hypotheses.

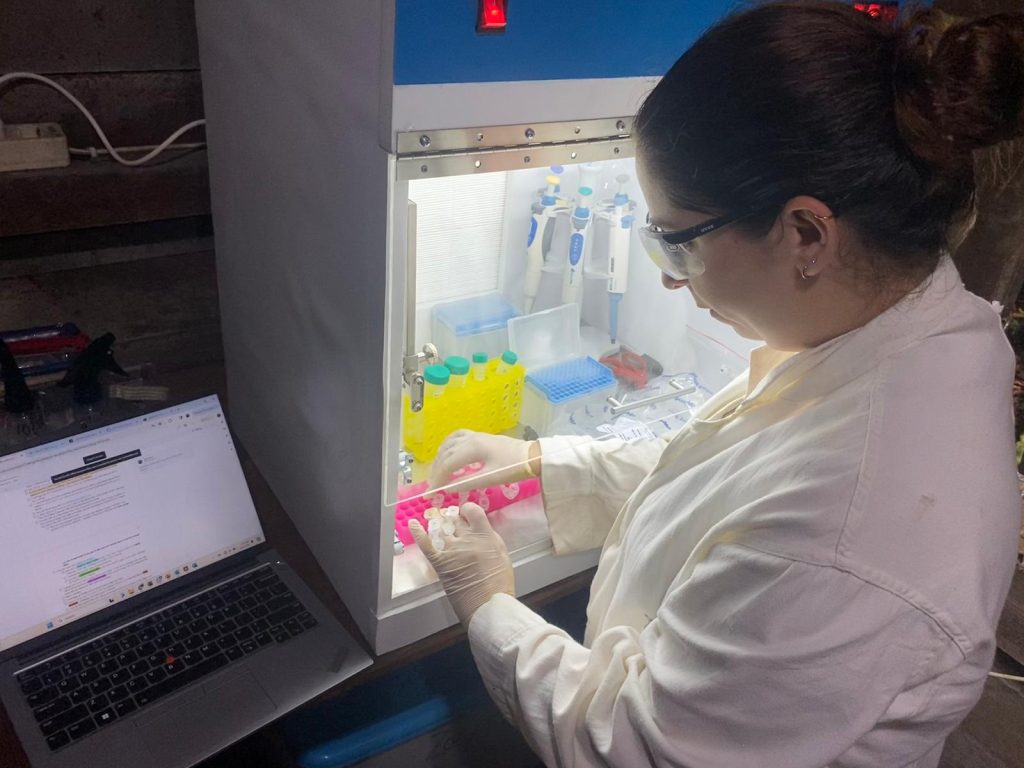

That brings us here: my dissertation field work and a year spent in the beautiful and biodiverse Gunung Palung National Park (GP). I knew that this would be difficult. We have a lab at Cabang Panti Research Station (CP) located within GP where amazingly talented laboratory assistants (Sumi, Ishma, and Ari) can perform protocols in parasitology, urinalysis, and fecal particle size analysis. However, prior to one month ago, genetics work, like that needed to conduct analysis on the gut microbiome, had not yet been conducted here. Thus, in preparation for my year in studying wild orangutans, I learned not only how to perform the protocols that I would need to analyze the gut microbiome, but how to successfully build a genetics lab in a remote rainforest. This would prove to require MacGyver levels of creativity. I would need to find smaller equipment than I was used to working with so that it could be transported to the field and could work with limited power, withstanding power outages. Some equipment was easy to find (like a mini-PCR machine designed for the field), others would involve more creative thinking (a nail polish shaker would be a stand-in for a vortex).

Recently, we had our first success in the lab. This, I hope, is a sign of good things to come. The first step in microbiome analysis, after samples are painstakingly retrieved off the forest floor thanks to the wonderful field assistants, is separating the DNA from the rest of the fecal sample. We do this by adding the feces to a tube half full of miniscule beads, that when shaken hard and fast enough, open the cells to release the DNA. This step involves the use of a piece of equipment known as a bead basher. It is essentially a large, motorized machine that mixes the sample non-stop for roughly 40 minutes. The first use of this machine presented us with a challenge. Rather than gyrating back and forth as it was supposed to, the machine began to exude white, billowy smoke. It was destroyed because of a voltage miscalculation and a lab juggling different types of power and power sources. After two weeks of waiting, a second machine arrived at camp. This time, we made sure to calculate the amount of power needed correctly and were met with a successful DNA extraction that we confirmed via DNA quantification! The next steps, I am sure, will present challenges as well. But, with the help of the amazing lab assistants who have supported me through both my failures and successes, I am confident that we will make it work.

Some days will almost certainly be frustrating, while others will be rewarding. One of the largest personal benefits of a lab in the field, is that when those frustrations do occur, I never need to walk more than 5 minutes to see a new plant or animal that I have only ever dreamed of seeing. This grounds me and reminds me why this work is important to science and conservation of natural places.

I will not only leave the physical lab behind when my year here is finished, but I will leave the Indonesian laboratory assistants, and any Indonesian University students who come here to learn, with the knowledge and skills to conduct their own genetics research. I believe this is a big step toward equity in our field. This will also hopefully eliminate the need to remove samples from the country, an arduous task that also eliminates work for local people. While I am passionate about conducting my own scientific research, I am equally passionate about making science accessible to others. Thus, while I will leave the field with data, I am hopeful that I will leave behind much more – not just a functioning genetics lab, but opportunities for Indonesian scientists who will work here in the future. While in Ketapang, prior to heading to the field, I had a chance to meet some of these future scientists at a local elementary school. Their eagerness to learn about orangutan conservation excited me about the future of conservationists and primatologists in Indonesia. I was also able to meet student scientists a little further on their journey while in Jakarta at Universitas Nasional (UNAS); several of whom will hopefully join me in the field for training in the upcoming months.

Lastly, I would be remiss to not thank my funders who have made this research possible. Work of this caliber is not only difficult, but it is expensive. Thank you to AMINEF/Fulbright Indonesia, Boston University Graduate Research Abroad Fellowship, and the David L. Goodman Scholarship committee. Thank you also to Dr. Cheryl Knott without whom this project would look so very different. Finally thank you to everyone who works with GPOCP. Because of you I am inspired to be a better scientist.

————-

Management of Cabang Panti Research Station is conducted by the Gunung Palung National Park Office (BTN-GP) in collaboration with GPOCP/YP. Scientific research is carried out in conjunction with the Universitas Nasional (UNAS) and Boston University.