By Cassie Freund, Program Director

“This is large-scale burning atop huge carbon stores that should not have ever happened.” – Robert Field, Columbia University/NASA

Orangutans along the Mengkutup River in Central Kalimantan search for a path amid thick, acrid smoke. Photo © Tim Laman.

Those of us keeping up with the news on the Indonesian forest fires have been inundated with information lately. And those of you who haven”t heard much news shouldn”t feel guilty – the Western media hasn”t been covering this issue nearly as intensely as the situation merits. That in itself is disappointing, since this has been called “the biggest environmental crime of the 21st century,” and “a crime against humanity of epic proportions.”

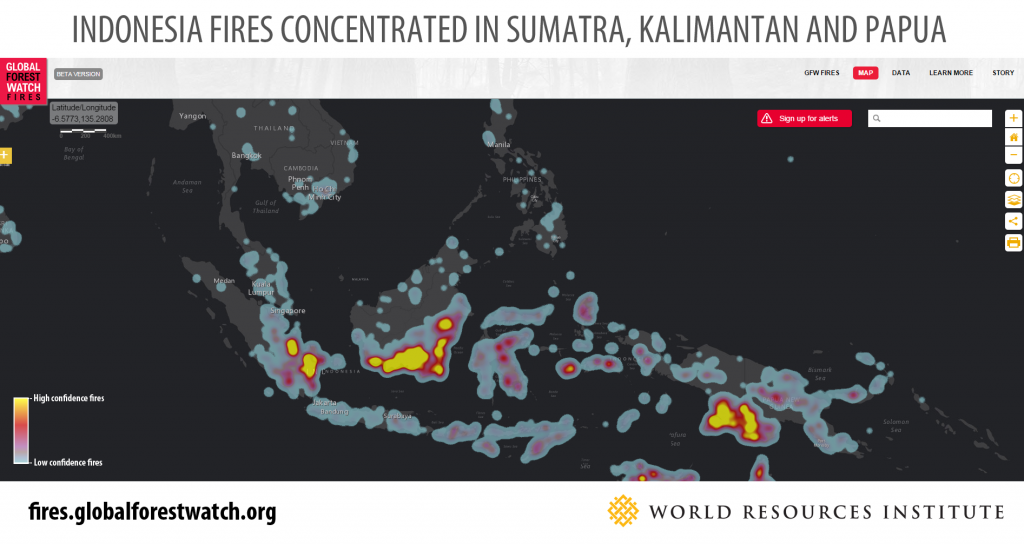

Let”s review: since mid-August, forest fires have been raging across Indonesia, with the majority of hotspots occurring on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. The resulting thick, choking haze has affected 43 million people. An estimated 500,000 people have contracted respiratory infections, and this is based on the number of people who have gone to the hospitals for treatment. The actual number is likely far higher as it doesn”t take into account people who live in remote locations without a nearby hospital, or those that are too poor to afford treatment. The official death toll is 19 people, many of them children. The smoke now blankets three-fourths of Indonesia and stretches as far as Thailand and the Philippines (over 1,000 kilometers away!) Approximately 2 million hectares of land have been or are currently on fire, most of it peat forest that under law should never have been developed. In case you”re having trouble imagining how big 2 million hectares is, it”s about 4 times the size of the island of Bali. This peat soil, which is a thick bed of decaying organic material, is essentially a massive carbon storage system. When drained and set alight, it becomes a carbon bomb. Most Indonesian people, including government officials know the basics about peat. So, why did this happen? It”s a confluence of multiple factors, including the political influence of large corporations, poor environmental planning and lack of government foresight, and this year”s strong, El Niño-fueled dry season. But, to be clear, the severity of this fire season was entirely predictable, and in fact scientists raised concerns about it many months ago.

“When people think about climate, they only think about smokestacks and tailpipes, and this is obviously the biggest climate story on the planet right now.” – Rolf Skar, Greenpeace USA

The negative effects of these fires are going to last far beyond this dry season. According to an analysis by the World Resource Institute, since September 1st the daily emissions from the fires have surpassed daily emissions from the entire U.S. economy 60% of the time. The total greenhouse gas emissions from the past three weeks have surpassed the yearly emissions of the entire country of Japan and are creeping up on Brazil. In addition to carbon dioxide, forest fires also emit methane, and the amount of methane stored in peatland forest is estimated to be over 10 times that stored in other forests. This, combined with the fact that peatlands are so carbon rich, means that these fires in Indonesia could be up to 200 times more potent, in terms of climate change, than wildfires in other ecosystem types.

Most years, the forest fires are restricted to Kalimantan and Sumatra, but this year, Papua has also seen many hotspots.

All told, Indonesia”s carbon emissions this year will be the second-highest in the country”s history, second only to the emissions from 1997 (also an El Niño year). Notably, hotspots have recently appeared in Papua, where palm oil is slowly moving in and the government has already begun opening peatlands for a mega agriculture project, called the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate, designed to increase domestic food production. In fact, 88% of the hotspots in Papua this month were in Merauke. This project is especially distressing in light of the utter failure of Indonesia”s first mega agriculture venture, Central Kalimantan”s ill-advised Mega Rice Project, where a million hectares of peat forests that were originally slated for conversion to rice fields now lay drained, degraded, and burned after it become clear that rice doesn”t grow on peat. If Indonesia is to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 29% by 2030, as they have reportedly pledged to ahead of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change”s upcoming COP-21 in Paris, they should seriously reconsider their intentions in Papua, in addition to committing to a thorough plan of canal blocking and peatland restoration, as well as to revoking all agricultural concessions in areas where the peat is deeper than three meters, in accordance with existing national laws. Taking these steps will mitigate future forest fire risk, and could prevent significant greenhouse gas emissions.

“The fires this year are similar to 1997, but far more severe because the smoke negatively affects so many lives. The impact of the fires harms the economy, biodiversity, human health, education, and clearly releases carbon emissions… biodiversity loss could include medicinal plants and rare species.” – Hartono, University of Gajah Mada

In addition to greenhouse gases, the peatland fires are also emitting ozone, ammonia, formaldehyde and carbon monoxide, another serious issue. While measuring air quality last week in Palangkaraya, one of the hardest-hit cities in Kalimantan, CIFOR scientists found carbon monoxide levels of 30 ppm in a hotel five kilometers away from the nearest fire. Considering that normal, healthy CO levels are less than 1 ppm, that”s pretty shocking! Although many people wear masks during the most polluted days, often normal surgical masks are insufficient to prevent negative health effects, and as of mid-October some more remote villages in Central Kalimantan hadn”t even received those. The government is now discussing evacuating babies and children from the hardest-hit areas of Borneo, but thus far no concrete plans have been made.

View from an airplane flying over Pontianak on October 20th. The thick smoke and poor visibility have caused thousands of flights all over Indonesia, and in neighboring nations, to be canceled.

We don”t yet know the effects that this will have on Indonesia”s orangutan population, but it”s not good. If people are suffering respiratory distress, wild orangutans certainly are as well. In fact, BOS Nyaru Menteng, the largest orangutan rehabilitation center in Borneo, has not ruled out the possibility of evacuating all 470 of its animals. The research stations at Sabangau and Tuanan, two long-term orangutan research sites that mostly encompass peat forests, are currently threatened by fires that show no sign of stopping. And, the most recent estimates suggest that a full one-third of Indonesia”s orangutans (20,000 individuals) are in danger as their habitats burn to the ground around them. As the forest is destroyed, orangutans and other species have been fleeing the forest to seek respite in local villages, where people are not always welcoming to wildlife. These animals, including proboscis monkeys and sun bears, are usually taken in as pets, and more often than not they die in captivity.

“There is no new solution to the issue as everyone understands what must be done. This is a matter of whether we are willing to resolve the issue” – President Joko Widodo, November 2014

Those of us who do research and conservation in Indonesia expect – and until now have grudgingly accepted – a certain amount of haze every year. But this year has been far beyond the limits of normal. This fire disaster, fueled by haphazard issuing of permits to oil palm companies, illegal and large-scale drainage and degradation of peatlands, and weak law enforcement of existing burning laws, has been a long time coming. While it”s not entirely the current administration”s fault, scientists have been sounding the alarm since June that this year is an El Niño year, and there were numerous actions that could have been taken to limit the haze. That being said, President Jokowi has been far more responsive than past leaders to the crisis, even traveling to Central Kalimantan to observe the firefighting action in person, and cutting last week”s scheduled visit to the U.S. short to personally oversee the crisis response. Hopefully now he takes advantage of this crisis and seizes the opportunity to prosecute rogue oil palm companies and strengthen environmental protection laws.

The forest fires are pushing many animals, such as this baby sun bear, into human territory, where they are in danger of becoming pets. Since the fires started, local authorities and animal rescue organizations have been overwhelmed by the number of cases like this one.

I don”t know what will happen in the coming weeks and months, how long this will last, or what it will mean for the future of Kalimantan”s rainforests and orangutans. What I do know is that dozens of our colleagues (and some of my closest friends) have been fighting fires, 24 hours a day, for weeks now, to defend some of this country”s last remaining orangutan habitat. I know that we”ve been living inside of a smoke blanket for months now, and blue sky is a distant memory. And I know that we cannot let this happen again. Within the next couple of months the rains will come and the fires will stop, but that won”t mean that the problem is over. We must work to fix the underlying issues, or this year”s disaster will be repeated in the future. For us at GPOCP this means increased lobbying of the local government for sustainable environmental management practices. Those of you at home can help by purchasing only products which use sustainably sourced palm oil. Additionally, you can help save orangutans in the most at-risk areas by donating to the ongoing firefighting operations in Kalimantan and Sumatra at redapes.org/firefund. Although this year has been devastating for Indonesia”s orangutans and their forest habitat, the silver lining is that the resulting public outcry will hopefully drive political change and positively impact conservation in the future.