By Cassie Freund, Program Director

One of the ongoing questions for the GP conservation team lies in how to best evaluate and measure our impact on orangutan conservation. Sometimes the effects of our activities, like wildlife crime investigations, are tangible and can be seen almost instantaneously, but our environmental education and conservation awareness programs present a challenge. How can we assess the impact of newspaper articles, radio shows, and the thousands of stickers and posters that we distribute each year, when the recipients are scattered across an enormous geographical area? This year we”ve tackled this challenge through a set of social surveys, administered to 200 people across Ketapang and Kayong Utara regencies. As an added bonus, we”ve been able to get our Bornean Orangutan Caring Scholarship (BOCS) recipients involved at every step of the process, challenging them to look at conservation in a new way.

- An example of a GPOCP billboard about the benefits of forest conservation from 2009.

- We created this billboard in honor of Orangutan Caring Week 2014.

Many wildlife conservation projects spread their message through billboards. GPOCP has also used this method in the past, but we haven”t erected any billboards in the past few years, making it a perfect project around which to build our evaluations. The design is simple: survey 100 people in each regency near the location in which we will put up conservation awareness billboards, analyze the data to understand what types of messaging regarding orangutan and rainforest conservation are needed, design the billboards based on the information obtained from the surveys, display them for three months, and then re-survey at these locations to find out if billboards are indeed an effective method of spreading our conservation message. With this experimental design in mind, the four BOCS students interning in our office this past summer were given the task of developing and administering the survey. The results were more interesting than we expected, and uncovered some key differences between the community in Ketapang city and those living in the rural town of Teluk Batang, on the north side of Gunung Palung National Park, information that will help us to better target our conservation messaging to these two different audiences.

Proboscis monkeys were correctly identified by many respondents as a species that is endemic to Kalimantan. Photo: Rizal al-Qadrie.

I”d like to share a few of the results here, to illustrate the importance of these data and the complexity of orangutan conservation. One of the things we asked people was about their knowledge of biodiversity, specifically if they could name some animals that are endemic to Kalimantan. People in Ketapang listed, on average, 2.3 animals each, and some people gave up to seven answers. In contrast, Kayong Utara residents named an average of about 1.8 animals, and the most any single person listed was three. Two of the most popular answers in each location were orangutan and proboscis monkey, but the other responses diverged widely. Ketapang residents also commonly listed hornbills and pangolins, other animals which are certainly emblematic of Borneo. Kayong Utara residents, on the other hand, listed deer (which are hunted for meat) and a certain bird species, the white-rumped shama, which is currently a popular species in the bird trade. This suggests that these groups of people have very different perspectives on the benefits of biodiversity; for one group, there is significant cultural value, whereas in the latter, biodiversity is used mainly for economic gain.

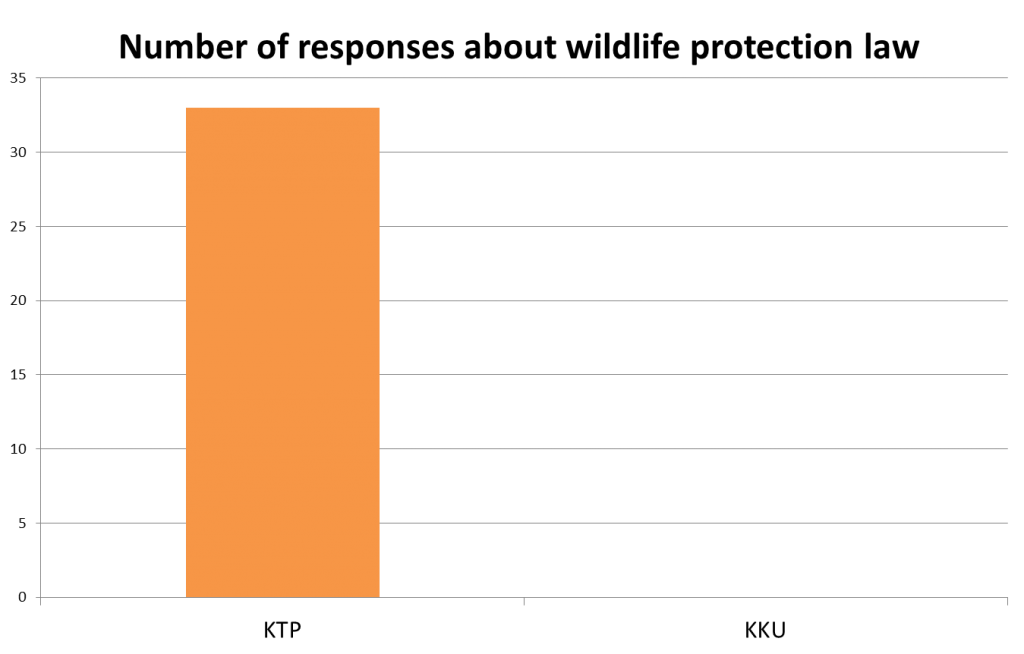

Another result that really surprised me was in response to the question, “Is it okay to keep an orangutan as a pet? Why or why not?” People in both places largely answered as we hoped they would, acknowledging that no, it is not okay. About one-third of the respondents in Ketapang supported their answer with the reasoning that orangutans are legally protected under Indonesia”s wildlife conservation law. However, in Kayong Utara not a single person mentioned the legal issue. Furthermore, when respondents who answered that it was okay (and even good) to keep orangutans as pets were asked why, there were two clear opinions on this. First, as expected, people want to have pet orangutans because they are funny and unique. This isn”t surprising; a significant portion of the wildlife trade is driven by the “cute-factor.” The second answer was somewhat unexpected: it appears that people believe that, because the forest is quickly shrinking and orangutans are going extinct, keeping one in their homes is actually a helpful form of conservation. This implies that people are hearing the message about the importance of the rainforest, and want to protect orangutans, but are going about it entirely the wrong way. This answer is something that we (and other orangutan conservation organizations) have been hearing more and more often recently, and clearly means that our collective message needs to be more nuanced if we are to prevent unwanted consequences. In my opinion, this example perfectly illustrates the importance of social survey data. We must listen to feedback from the communities to understand the true impact of our actions, and tailor them accordingly to guarantee a positive impact!

Doing these kinds of surveys can sometimes get depressing when we realize just how much more work there is to be done. However, there are some positive conclusions that we can draw from this exercise as well. First, several respondents made the comment that “animals also want to be free, like humans,” which is a powerful statement. It shows that a sense of empathy for biodiversity is developing in these communities, which hopefully will continue to grow into a powerful source of conservation action. The second major conclusion that I”ve drawn from these data is the importance of environmental education. The results of the survey show a very clear difference between Ketapang and Kayong Utara, with Ketapang respondents across the board showing more knowledge about and positive attitudes toward conservation. This seems counter-intuitive at first glance. Ketapang residents live in the city, and aren”t necessarily very dependent on the rainforest for their lives, whereas people in Kayong Utara are still very dependent on the forest, both economically and in terms of ecological services. However, GPOCP”s main office is in Ketapang city, and over the past 15 years we”ve worked in virtually every school in the city to teach students of all ages about the importance of orangutans and their rainforest habitat. Our work has more recently been supplemented by other conservation organizations who are also based here in the city. Education is an incredibly important factor in saving wildlife and habitats, and highly educated communities are more likely to care about conservation – a conclusion which is clearly supported by these social survey data.

This simple graph shows a dramatic difference between the number of respondents in Ketapang and Kayong Utara who are conscious of Indonesia”s wildlife protection law, and will help guide our environmental education efforts in Kayong Utara in 2016.

With this information in hand, last week we worked with the BOCS recipients to design two conservation-themed billboards based on the real-world data they collected, and we will produce and display them during the first quarter of next year. In addition to hanging the billboards, we”ll also be sharing the results of our survey with the local government in an effort to help them better target their own conservation activities. We”ve certainly got our work cut out for us in 2016. Stay tuned to our social media feeds (linked in the sidebar) to keep up-to-date on our progress! Special thanks to Orangutan Outreach, who have funded every step of this project along the way.